Berlin, Germany

David Chipperfield Architects

Post By:Kitticoon Poopong

|

| Photo © Courtesy of SPK/Ute Zscharnt--The Neues Museum’s west elevation can be reached via bridge over the Spree. |

David Chipperfield Architects with Julian Harrap brings Berlin’s Neues Museum to life.

Until the Neues Museum reopened last fall in Berlin, few visitors knew about this quietly palatial edifice built between 1843 and 1859. Located to the north of

Karl Friedrich Schinkel’s magnificent Neoclassical Altes Museum (1824–30) on

Museum Island, a

UNESCO World Heritage Site, this conventionally dignified four-story museum was designed by

Friedrich August Stüler, one of Schinkel’s leading pupils, to didactically display archaeological finds of

the prehistoric, ancient Egyptian, and Classical eras. Stüler had a good client:

Frederick William IV, who took over the Prussian kingdom in 1840, also studied architecture with Schinkel, as Joseph Rykwert recounts in Neues Museum Berlin: David Chipperfield Architects in Collaboration with Julian Harrap (2009). It was the king’s idea to devote a part of an island surrounded by the

Spree River in central Berlin to a monumental architectural ensemble that attested to Germany’s intellectual and artistic stature.

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons/Gryffindor stitched by Marku8--The Neues Museum’s west façade includes a rebuilt wing at its north end, which was destroyed in World War II. |

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Achim Kleuker--The design of Friedrich August Stüler’s Neues Museum’s Neoclassical main entrance façade has been restored along with the Doric colonnade in front. David Chipperfield Architects with Julian Harrap as the restoration architect were in charge of the project. |

Unfortunately, the Neues Museum was heavily bombed in World War II and halfheartedly repaired by the East German government before the country’s reunification in 1990. After decades of disuse, it is now conserved, rehabilitated, reconstructed, and remodeled by Chipperfield, with Harrap as the restoration architect. Since its October 2009 opening, the Neues has been drawing crowds to the cluster of five 19th-century museums on the island, including the Bode, the Pergamon, the Alte Nationalgalerie (Old National Gallery), and Schinkel’s Altes. In 2013, a Chipperfield-designed visitors’ center, the James Simon Center, will open to the west of the Neues as part of the architect’s master plan.

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Achim Kleuker--On the second level, the gallery along the southeast side displays artifacts from Roman provinces in the delicately scaled vitrines. Columns with Ionic capitals, fluted columns, and mottled walls enhance the elegance of the effect. |

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Achim Kleuker--The second-level gallery on the southwest wide of the museum is devoted to displays of the barbarian invasions and the Middle Ages. Marble columns with Ionic capitals contrast with the new flat ceiling of precast concrete. |

|

| Photo © Courtesy of David Chipperfield Architects--On the second level, along the east wall, a hall connects the north and south galleries. It features a Roman statue of a boy (“Knabe von Xanten”) and Pompeian murals and piers. |

Chipperfield and Harrap’s accomplishment with the Neues is prodigious. Their approach, like that of the 1964 International Charter of Conservation and Restoration of Monuments (aka the Venice Charter) calls for exposing changes that have occurred through time, rather than returning a building to its original condition, often as a facsimile. Scores of architects and consultants have labored on the $255 million project since 1997, when Chipperfield won the commission, after a drawn-out competition process that began in 1993. The result is a stunningly haunting setting that brings to the foreground fragile traces of history in the palimpsest of its walls, ceilings, floors, and columns. The ensemble offers a richly layered and sometimes coolly austere backdrop for Berlin State Museums’ Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection, the Museum of Pre- and Early History, and artifacts from the Collection of Classical Antiquities that the building houses. With one or two cavils (more about these later), the restoration/modeling and installation design reflect the influence of the pathbreaking direction set forth by Franco Albini and Carlo Scarpa in their postwar museum renovations in Italy, such as Scarpa’s Castelvecchio in Verona (1964).

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Achim Kleuker--The enfilade of main-level galleries extending from the south to the north creates a dramatic series of portals in different architectural styles. |

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Achim Kleuker--The restored gallery on the main level’s southeast side features terrazzo floors, fluted columns and Doric capitals, some of the original murals, and a shallow vaulted ceiling. The restored gallery on the main level’s southeast side features terrazzo floors, fluted columns and Doric capitals, some of the original murals, and a shallow vaulted ceiling. |

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Achim Kleuker--A gallery on the southwest side of the main level has a shallow vaulted ceiling formed of clay pots, roughly rendered columns, and terrazzo floor. |

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Christian Richter--The columns of the main stair hall on the second level still show their battle scars, including bullet holes. The new gallery for sculpture along the northwest wall lies beyond. |

The Neues and its contents suffered a number of changes since it first opened, including a gallery modernization in the 1920s (which featured hung ceilings) and, more traumatically, the Allied bombings in 1943 and 1945. The war destruction left the stair hall as one big hole and the northwest wing and domed southeast corner a shambles. In the postwar years, repairs and shoring up of the structure kept the unused ruin intact.

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Achim Kleuker--On the second level, a gallery extending across the eastern front of the building now houses vitrines displaying the Egyptian Book of the Dead. Stüler’s bowstring trusses with zinc and brass ornament have been restored. |

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Stiftung Preusserischer Kulturbisetz/Ute Zschartnt--In the Prolog gallery of the main level the Italian architect Michele de Lucchi has designed elegantly linear glass and metal vitrines. The wainscoting is faux graining on plaster. |

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Achim Kleuker--On the south end of the main level is the gallery devoted to Heinrich Schliemann’s archeological discoveries at Troy in the latter part of the 19th century. A bay window overlooks the Greek Courtyard, a shape echoed in the series of shallow domes composed of clay pot construction. |

In working with the approximately 220,660-square-foot palatial block, where galleries are organized around two courtyards flanking the monumental stair hall at the center (which Chipperfield rebuilt), the architects didn’t want to draw a hard line between what Chipperfield did with the new and Harrap with the old. Their collaboration demonstrates they could work out an approach that incorporates a certain philosophy about fragments (“They needed to be put back in a meaningful context,” says Chipperfield), and about gaps in the original building fabric (“We realized when a gap is about 10 centimeters [4 inches], it’s quite easy. When it’s 2 meters [6½ feet], it’s a bit more difficult; and when it’s 20 meters [65½ feet], it’s something completely different”). In filling in the gaps, Chipperfield sought to retain a sense of unity by introducing a concrete aggregate that would both identify and link the new interventions. This precast concrete, formed of white cement, sand, and Saxonian marble chips, provides the dominant material for galleries in the northwest wing, the main stair hall and its enclosing walls, and the post-and-lintel platform structure inserted in the Egyptian Courtyard. (The Greek Courtyard, on the eastern side of the museum, has been left pretty much intact, although like the Egyptian Courtyard, it receives daylight from an expansive glass-and-steel roof.)

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Achim Kleuker--The entrance vestibule of the Neues Museum opens onto the newly built grand stair leading to the large stair hall on the second level. |

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Achim Kleuker--In the lowest level of the museum, brick barrel vaulted rooms contain displays devoted to the Egyptian collections. |

|

| Photo © Courtesy of SPK/Ute Zscharnt--The second-level stair hall has sandblasted concrete walls that define the staircases to the third level. Recycled brick and terra cotta provide major materials for the enclosing walls, while the ceiling is formed of timber trusses. |

In addition, a number of new walls and ceilings needed to be reconstructed. To do so, the team found 1,350,000 bricks from buildings throughout Europe to create the now-exposed surfaces, often supported by a new poured-in-place concrete structure. The most effective use of masonry occurs in the stair hall, where reddish industrial brick and edge-laid terra-cotta tiles animate upper walls once dominated by historically themed murals, since destroyed. Both new exterior and interior brick walls are treated with a thin mortar slurry to give the brick a muted tone, a coloration approach found elsewhere in variegated wall finishes that highlight differences in the ages of the surfaces. An impressive display of the recycled brick occurs in the rebuilt southeast dome, where beehive corbeling surrounds majestic Roman statues. Topped by a lantern of sandblasted glass and metal, the space in the daytime seems suffused with the eerie half-light of the interior of Schinkel’s nearby Neue Wacht (Royal Guard House).

|

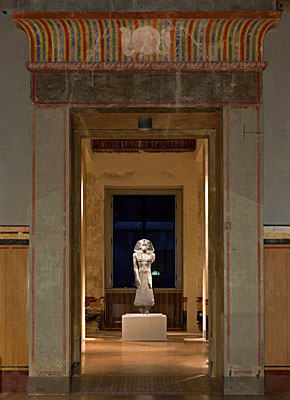

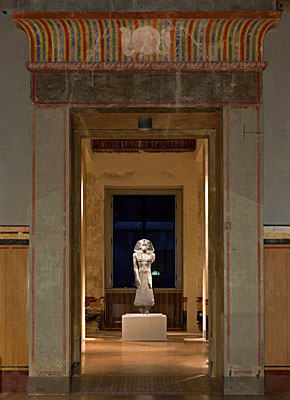

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Achim Kleuker--An enfilade of galleries on the main level frames a statue of Amenemhet III, 1850 B.C., which stands in the room at the end of the Prolog gallery. |

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Achim Kleuker |

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Achim Kleuker--A view looking up from the floor of the Greek Courtyard shows the new skylight, the apse on the south side of the court, as well as the restored frieze of “Last Days of Pompeii,” created for Stüler’s space by Heinrich Schievelbein. |

Elsewhere, Chipperfield and Harrap have re-created the shallow, lightweight domes made of clay pots that Stüler had introduced to lighten the load on the foundations resting on marshy soil. Harrap, who is incidentally the restoration architect for Sir John Soane’s Museum in London, notes that when Schinkel traveled to England in 1826, he took Stüler along. The two visited Soane’s house-museum and his Bank of England, where they were particularly taken with the hollow clay pots Soane used for his lightweight vaults. Years later, Stüler put them to use in the Neues. But since many of the clay pots were missing by the time Chipperfield and Harrap arrived on the scene, they had to find a company that would produce 40,000 in order to rebuild the domes, which, now exposed, enliven a number of galleries. In addition to the domes, Chipperfield and Harrap restored the cast- and wrought-iron bowstring trusses in second- and third-floor galleries. These are yet again examples of Stüler’s interest in the new technologies of the 19th century, as Kenneth Frampton points out in an essay in Neues Museum Berlin.

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Candida Höfer/ Verlag der Buchhandlung Walter König--The new concrete structure inserted into the Egyptian Courtyard allows views from the main level to the sarcophagi below. |

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Christian Richter--On the third level, Stüler designed a “star” room in the Gothic style in the southeast corner of the floor. The room has been restored very simply. |

“

We had a rule at the outset,” says Chipperfield. “No false walls, no ducts, no false ceilings.” Naturally, there are exceptions: “If a new room needed a roof and ceiling, then services could be inserted in them. But if the historic ceiling remained, the team found another way to solve the air handling and electricity.” The insertions are subtle, and like the overall approach, differ thoughtfully and dramatically from room to room.

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Achim Kleuker--In the Egyptian Courtyard, a platform structure creates a second-level gallery for art objects encased in the vitrines. |

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Achim Kleuker--A new gallery in the rebuilt portion of the northwest wing displays sculptures in glass vitrines designed by Michele de Lucchi. |

Chipperfield’s architecture in Germany, as shown by his austerely elegant Modern Literature Museum in Marbach, reveals an affinity for the principles of the Romantic Classical masters Friedrich Gilly, Leo von Klenze, and, of course, Schinkel. In Marbach, Chipperfield also used precast concrete, but with an aggregate formed of limestone, instead of marble. Oddly, the Neues concrete, with its sandblasted marble chips, appears dead. Where it is polished—such as the balustrades and stair treads—the aggregate contains larger marble chips and emanates a warm glow. However, the deadliness of the sandblasted concrete dominates. It may change according to the light—but this observer saw the concrete aggregate at different times on several wintry gray days. And at night, the electric light from spots embedded in the oak trusses of the stair hall is unfortunately bleak. So the concrete aggregate, in all its asperity, looks morguelike. Elsewhere, lighting fixtures installed in concrete ceilings evoke an office-park ambience. That said, the lighting, particularly in Michele de Lucchi’s bronze vitrines, generally works to great effect.

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Candida Höfer/ Courtesy Verlag der Buchhandlung Walter Köni--Queen Nefertiti’s bust (1351 B.C.) is the only object on display in the coffered North Dome on the second level. |

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Achim Kleuker--A bronze-and-glass balustraded bridge links a second-level gallery on the north to the platform in the center of the Egyptian Courtyard. |

All in all, the contrast between the new (austere, sometimes too cold) and the old (intellectual, romantic, richly layered with history) at least allows you to know what came before and what did not. But it is the old that grabs you.

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Achim Kleuker--A third-level gallery retains Stüler’s bowstring trusses as well as the original 19th-century vitrines. |

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Achim Kleuker--On the main level, Stüler had originally installed panels of wallpaper with Egyptian hieroglyphs on the ceiling of the “Prolog” gallery. In the 1920s, the wallpaper panels were covered by a hung ceiling, which has been removed, and the panels restored. |

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Achim Kleuker--The South Dome room on the second level is reconstructed in a beehive form with recycled bricks. Sandblasted overlapping panels of glass compose most of the skylight. |

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Christian Richter--The Greek Courtyard in the museum’s south wing is shown with the restored frieze of “Last Days of Pompeii,” by Heinrich Schievelbein, prior to installation of the other exhibited works. |

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Zentralarchiv--The World War II bombings destroyed the South Dome at the corner of the main entrance façade. |

|

| Photo © Courtesy of Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB)/Zentralarchiv--During World War II, the second level of the main stair hall was gutted. |

|

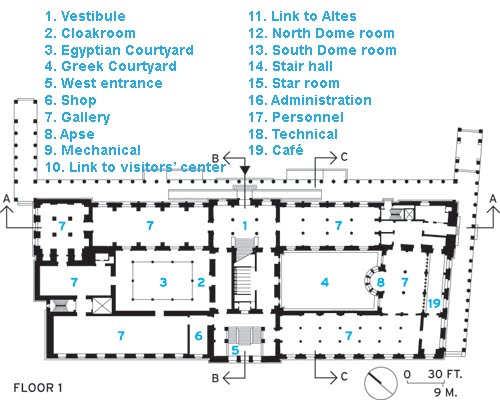

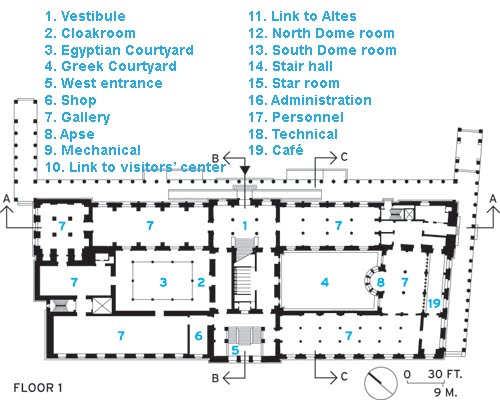

| level 0 floor plan-drawing Courtesy of David Chipperfield Architects |

|

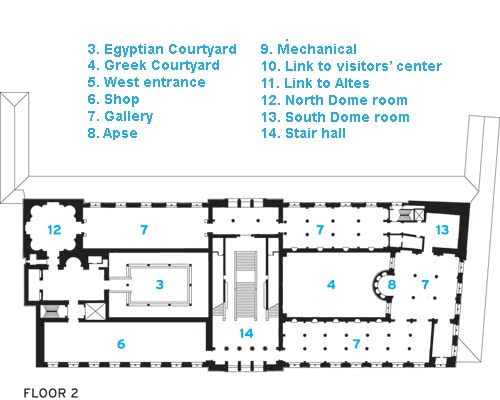

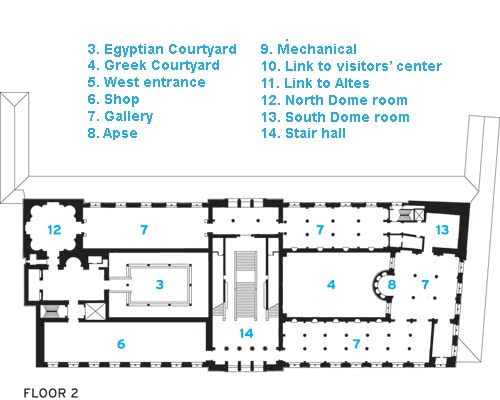

| level 1 floor plan-drawing Courtesy of David Chipperfield Architects |

|

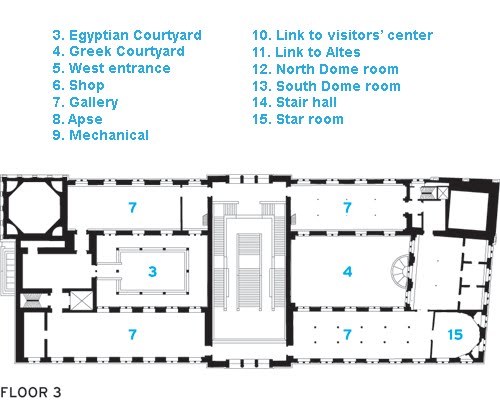

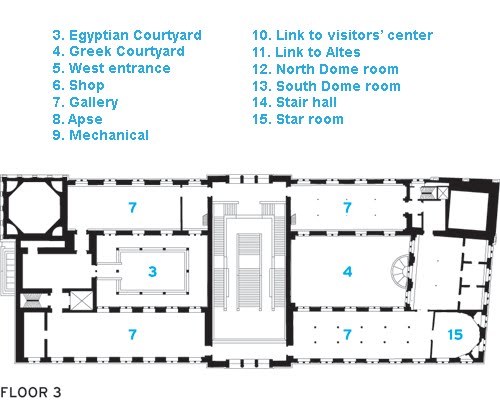

| level 2 floor plan-drawing Courtesy of David Chipperfield Architects |

|

| level 3 floor plan-drawing Courtesy of David Chipperfield Architects |

|

| level 4 floor plan-drawing Courtesy of David Chipperfield Architects |

|

| section A-A-drawing Courtesy of David Chipperfield Architects |

|

| section B-B-drawing Courtesy of David Chipperfield Architects |

|

| section C-C-drawing Courtesy of David Chipperfield Architects |

|

| section C-C-drawing Courtesy of Art +Com, 2008--A model shows Shinkel’s Altes Museum in the foreground, with the Neues behind, along with David Chipperfield’s design for the new visitors’ center on the west. |

The people

Architects: David Chipperfield Architects

Location: Berlin, Germany